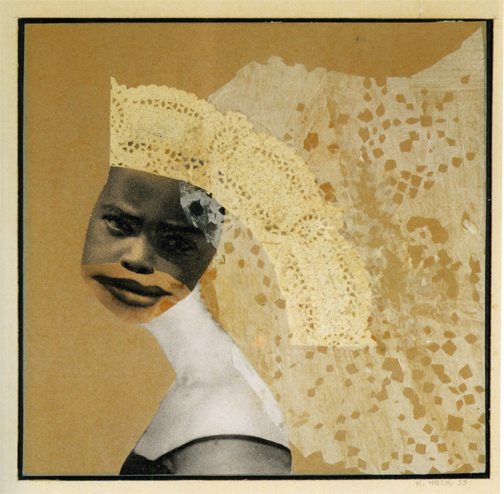

When a retrospective of Hannah Höch’s greatest works went on display at Whitechapel Gallery in London earlier this year, many people walked in asking, “Who?”

Höch was one of the unsung heroines of graphic design. She single-handedly created the photomontage as an art form during her years as a leader of the Dadaist movement in Weimar Germany. Berlin in the 1920s was a wild social frontier where it seemed like anything was possible. The Kaiser had abdicated, women began wearing pants, and mind-bending silent films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari were turning the world inside out.

In addition to Hoch’s visual mash-ups, works of the Dadaists included experimental painting, sculpture, fonts and arrangements that could not be called art. “Art is dead!” said the Dadaist. “Long live the Machine Art.” Dadaists said that pursuit of logic had lead Western culture down a dead end of sharply divided classes and enforced conformity. They wanted to tear down the old world, which they could see crumbling down around them between World Wars. They sought to unleash people’s natural creativity by encouraging chaos, nonsense, and irrationality. Höch and her collaborators sought to break down logic and reason, replacing them with dream imagery and pure aesthetics. In her role as a leader in the short-lived Dadaist movement, Hoch challenged old world ideas and popular cultural images about women at the same time.

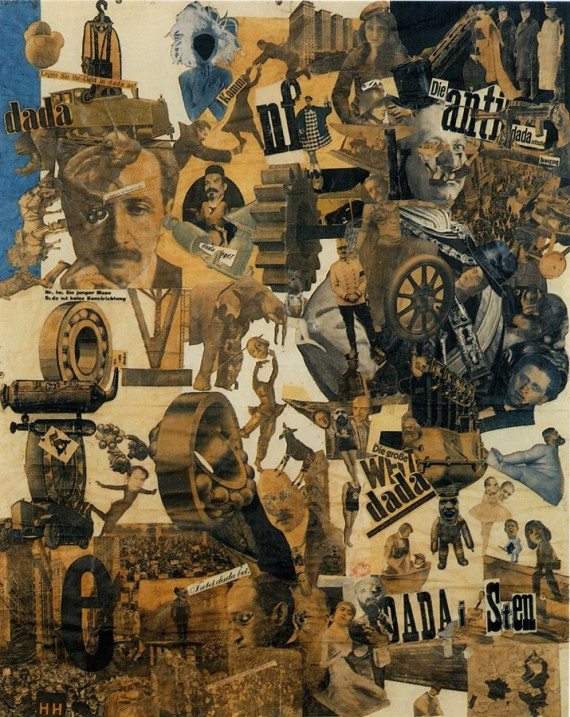

At the height of her graphic design artistry, Höch created a visual smorgasbord with her delightfully anarchic Cut With the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany. She balanced political commentary, social critique, intellectual curiosity, and joyful nonsense in a multi-layered whirl that succinctly defined her era. That masterwork was just the beginning of her career that would juxtapose elegant, arresting, and eternal images made out of shards from sources like European history, African tribal culture, and abstract forms. Her creations are dreamlike – often nightmarish – but always uncomfortably familiar. Toward the end of her life, her creations became more serene and surreal. They turned inward for a glimpse of what the Pop Art movement would later explore with unbridled optimism.

Photomontage and collage with watercolor, 44 7/8 x 35 7/16 (114 x 90 cm)

Seeing Höch works from different decades all together in one place, such as in the Whitechapel exhibit, gives the impression of watching the Internet being born. There are forms of women mixed with statues, machines, birds, icons, and mesmerizing patterns. The San Francisco Arts Quarterly best summed up what her designs do for the viewer:

“Höch’s work is ambiguous, but this allows for a sort of fluid and ‘fantastic’ reading. The medium she uses is surrealistic – the multifaceted layers of cut and pasted images relax the boundaries of interpretation, and therefore we can read them in myriad ways. Her work is both political and poetic.”

That may be why so many male artists of the time did their best to forget her. They simply couldn’t match her mysterious skills with a kitchen knife.

More images available on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VxlojUBxjj8